Prosecutor’s Chicago gang investigation ended in disaster. Then she became evidence gatekeeper

Former federal prosecutor Erika Csicsila spearheaded Operation Snake Doctor. In the wake of the investigation's overturned convictions and civil rights lawsuits, she tried to block disclosure

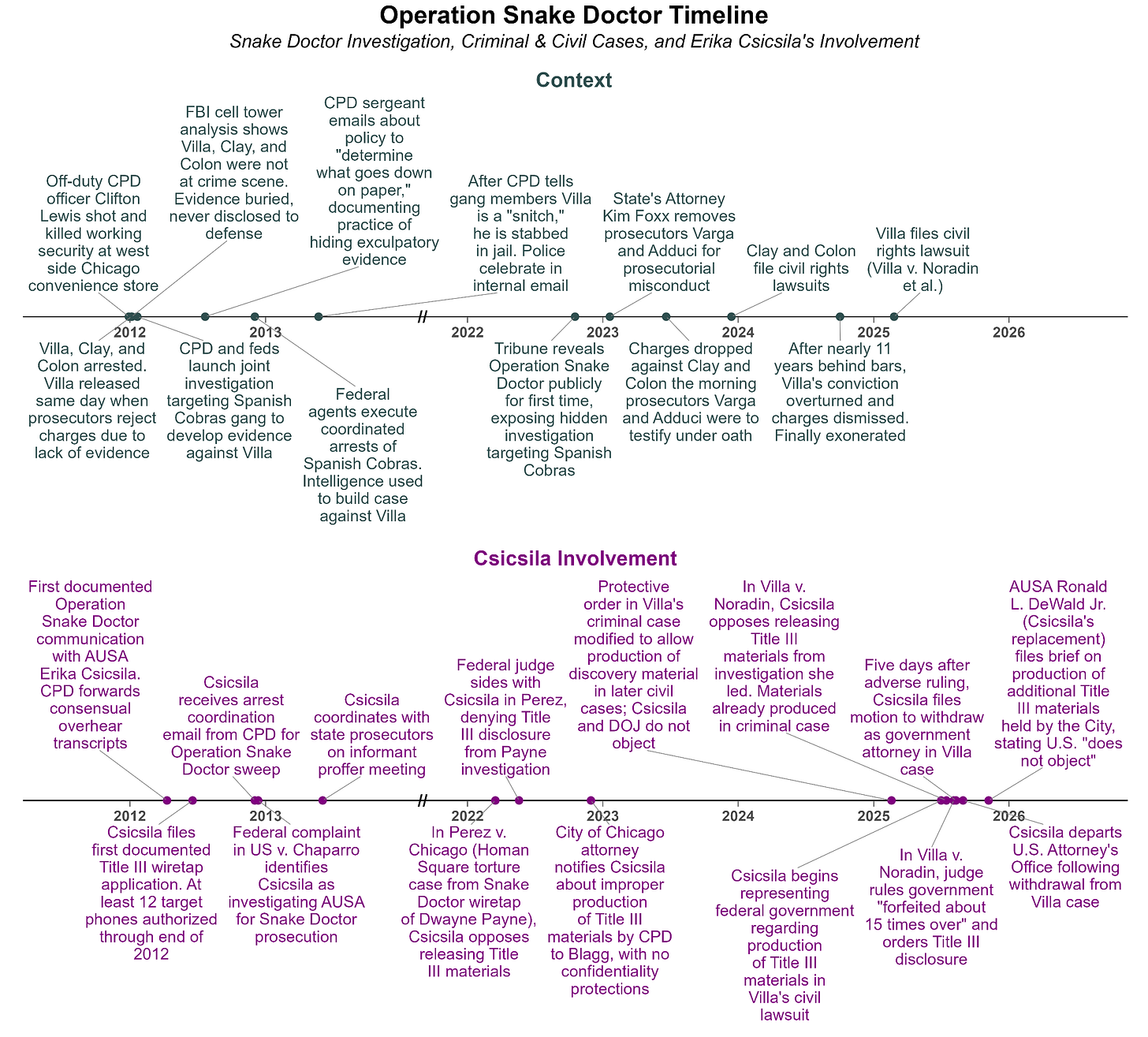

Plaintiffs in ongoing civil rights lawsuits are seeking redress for Operation Snake Doctor, a sweeping Chicago Police and federal investigation that ended in overturned homicide convictions, and allegations of torture, coerced confessions and fabricated evidence. But court filings show that the Assistant U.S. Attorney (AUSA) who coordinated the investigation went on to control the government’s response to requests for production of Snake Doctor wiretap materials and argued against their disclosure – meaning a key architect of the since-discredited operation was placed in charge of policing her own work and opposed production of materials that could raise scrutiny of her role.

Former AUSA Erika Csicsila played a leading role in Operation Snake Doctor from early 2012 to 2013 and worked extensively on wiretap efforts, but later argued against production of Snake Doctor wiretap-related materials in two civil rights cases stemming from the investigation. Csicsila successfully argued against disclosure in the first case in 2022. In a July 2025 filing for the second case, she took the same anti-disclosure stance, using the ruling from the first as legal precedent in her arguments, even though the wiretap materials at issue were already possessed by the plaintiff due to prior improper production by the Chicago Police Department (CPD) in his earlier criminal trial. The judge rejected Csicsila’s position, finding the government had “forfeited” its objections through “meaningful inaction” – failing to object when the protective order in the criminal case was modified to allow the materials into civil litigation. A protective order in this context is a court order restricting access to documents produced in the case and how they can be used.

Csicsila, who by this point was chief of the entire criminal division of the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of Illinois, withdrew from the case days later, and left the Department of Justice (DOJ) entirely that same month. Strikingly, Csicsila’s replacement took the opposite position on Title III disclosure and acquiesced to production of a new set of wiretap materials not previously produced to the plaintiff.

Taken together, it appears that a leading architect of Operation Snake Doctor and its wiretap surveillance component sought to block production of materials related to the investigation’s wiretaps in two subsequent civil rights lawsuits, even when in the second the plaintiff already possessed the materials from his prior criminal case. The fact that Csicsila’s replacement took the opposite position consenting to production under a protective order, even for additional materials the plaintiff had never seen, coupled with Csicsila’s abrupt withdrawal from the case and then the DOJ, make her anti-disclosure position all the more significant.

Multiple legal experts told Noir News that Csicsila’s dual-role was problematic given her extensive involvement in the criminal investigation.

“I would say it’s not best practices for a prosecutor who’s been immersed in an adversarial role in a criminal proceeding to then show up in a subsequent civil rights lawsuit,” said Abbe Smith, Director of the Criminal Defense and Prisoner Advocacy Clinic and Professor of Law at Georgetown University. “I think most careful, conscientious prosecutorial agencies, state or federal, would say this is a person – she has a dog in this fight. She has an interest. So she wouldn’t be the best person.”

Michael Cassidy, an expert on prosecutorial ethics at Boston College Law School, said Cscisila’s conduct could constitute a violation of Rule 1.7 of the American Bar Association’s Model Rules of Professional Conduct (“Conflict of Interest: Current Clients”).

“A lawyer is not supposed to represent a client if there is a significant risk that the representation will be limited, materially limited by – and then there’s a list of things, and one of them is the personal interests of the lawyers,” Cassidy said. “So, the question is whether she could be hiding any of her misconduct in the wiretap by trying to withhold the wiretap materials. If she could be, then you could possibly have a 1.7 problem, and somebody else from the government should be representing the U.S. Attorney’s Office there rather than her.”

“It seems to be like she’s just trying to cover up for the mistakes that she’s done and protect the people that, you know what I mean, that she was helping do these bad things to begin with, honestly,” said Jill Cremeans, a San Diego criminal defense attorney who has confronted obstacles to disclosure from the federal government in an ongoing case against the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

Operation Snake Doctor

Operation Snake Doctor was a joint local-federal homicide and narcotics investigation targeting the Spanish Cobras, a Chicago gang, following the December 2011 shooting of CPD officer Clifton Lewis. Lewis had been working an off-duty security shift at M & M Quick Foods, a convenience store in Chicago’s Austin neighborhood, when two masked men entered the store, one of whom shot Lewis. Shortly after the killing, law enforcement figured members of the Spanish Cobras were responsible, and eventually concluded Alexander “Flip” Villa pulled the trigger, Tyrone Clay entered the store with him, and Edgardo Colon was the getaway driver.

Throughout Operation Snake Doctor, CPD, the U.S. Attorney’s Office and the DEA used narcotics arrests and wiretaps to garner homicide evidence and secure federal narcotics convictions for Spanish Cobras not involved in the killing.

Csicsila was a leading architect of Operation Snake Doctor, exchanging hundreds of emails with CPD officers and federal agents, including some of the CPD officers named as defendants in the civil lawsuits, per emails and email metadata obtained by Noir. She also served as one of two federal prosecutors on narcotics cases against other Spanish Cobras. An attorney for the City of Chicago described Csicsila as “the lead on the Snake Doctor investigation,” in a hearing in one of the lawsuits.

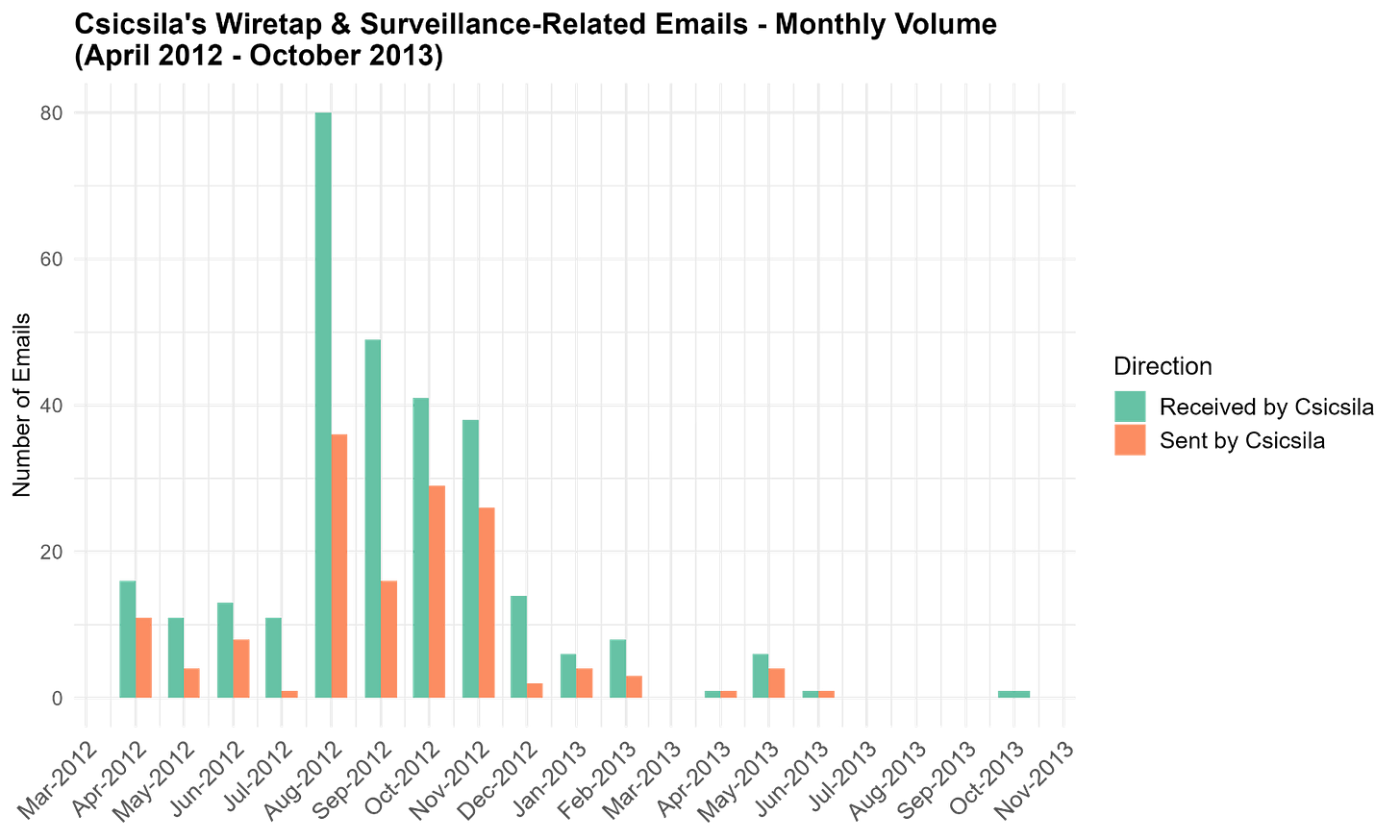

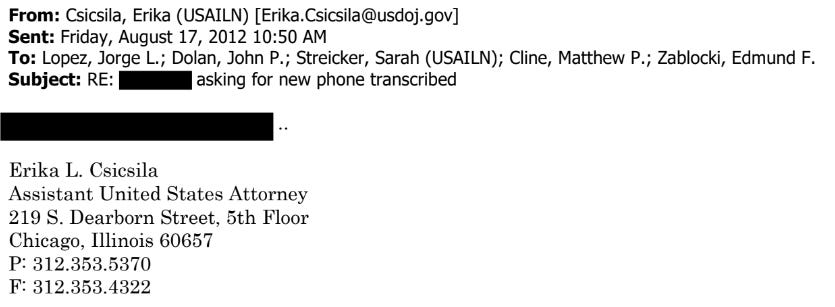

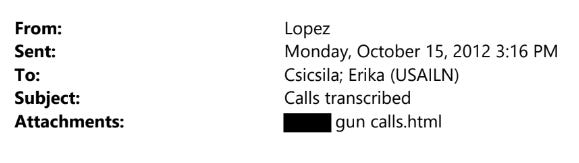

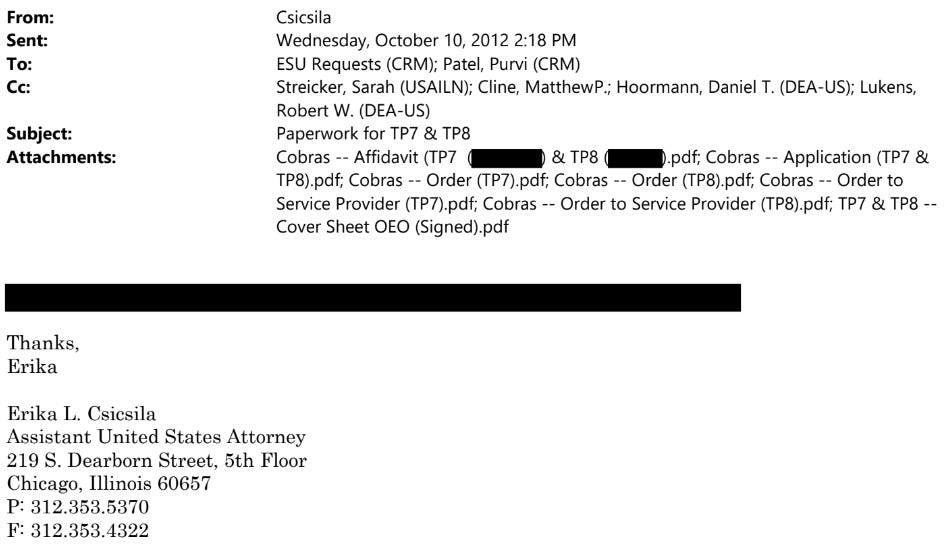

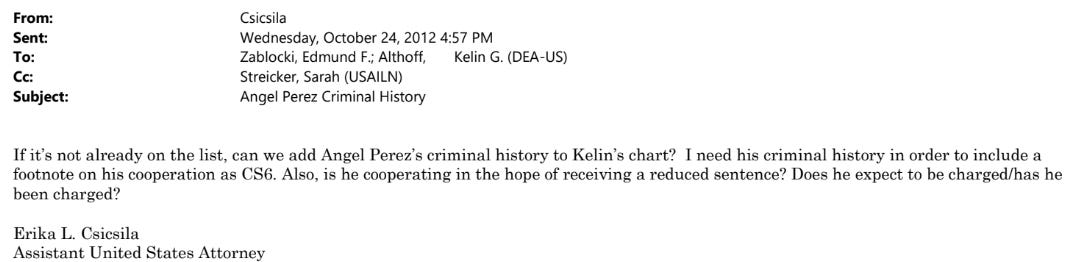

A large share of Csicsila’s email correspondence obtained by Noir pertained to Title III wiretap efforts in the investigation (court-authorized electronic surveillance under Title III of the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968). From April 2012 through October 2013, Csicsila sent and received at least 146 and 296 emails, respectively, relating to wiretaps and other surveillance efforts. These communications spanned the full spectrum of wiretap and electronic surveillance operations, from initial pen register coordination in April 2012 (pen registers capture metadata on phone communications) through Title III wiretap applications beginning in late April and extensive active monitoring that continued through late 2012, with follow-up activity extending into 2013. The wiretap surveillance appeared to track at least 12 different target phones (designated TP1 through TP12), with Csicsila coordinating Title III applications, daily “line sheets” documenting intercepted communications, 10-day progress reports, and analyses of specific “toll hits” and voice identification.

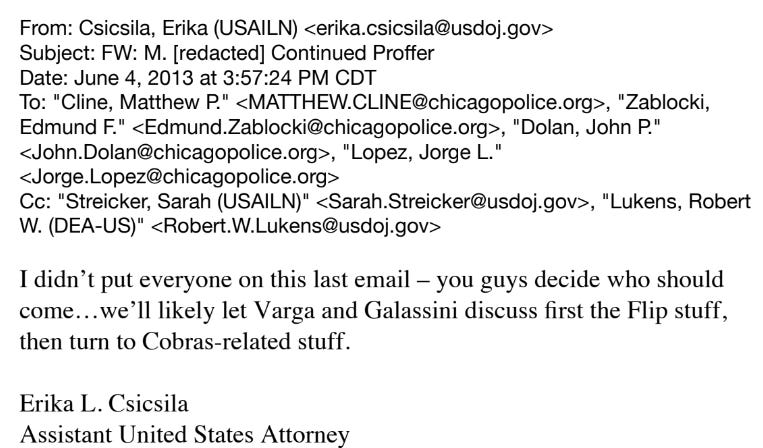

Csicsila’s involvement peaked in the fall of 2012: from August through October, she sent or received over 250 wiretap and surveillance-related emails, with 116 in August alone. The email traffic reveals Csicsila functioned as the central coordinator between federal wiretap authorization and local police investigative execution, coordinating closely with multiple CPD Gang Investigations officers, including Sergeant Matthew Cline, Officer Edmund Zablocki, and Officer John Dolan – and fellow Assistant U.S. Attorneys Sarah Streicker and Matthew Madden, along with federal agents such as DEA Special Agent Robert Lukens.

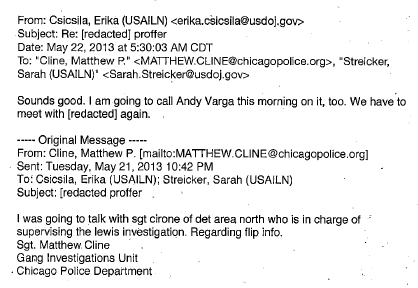

The cops and feds’ efforts paid off in the short term. Cook County prosecutors secured state level murder convictions for Villa and Colon, and Clay remained in jail for over a decade. Meanwhile, Csicsila prosecuted at least seventeen federal narcotics and weapons charges on Snake Doctor affiliates. Csicsila was also involved in the state criminal cases, exchanging emails with state prosecutors in 2012 and 2013 about proffer sessions and the status of the state prosecution, per court filings. A proffer session is a meeting where a witness or defendant provides information to prosecutors, usually in exchange for potential leniency or immunity. In at least one instance, Csicsila directly coordinated, and potentially participated in, a proffer session in June 2013, alongside state prosecutors.

Then Jennifer Blagg, a post-trial attorney for Villa, started digging.

Blagg discovered a potentially exonerating cell tower analysis, conducted by the FBI in 2012 and provided to state prosecutors, hadn’t been turned over to Villa’s original defense team, per the National Registry of Exonerations. The analysis seemed to show Villa, Colon, and Clay were not at the scene of the crime, nor were they together that day. She also discovered the prosecution failed to turn over a potentially exonerating cell phone extraction report and information regarding alternative suspects. The sweeping nature of Operation Snake Doctor – which saw CPD and federal authorities interrogate over 100 people in relation to the homicide – also wasn’t disclosed.

Under precedent established by Brady v. Maryland, the state is required to produce any exculpatory or material evidence to the defense even if not explicitly requested. The Brady violations Blagg discovered were central to Villa and Colon’s convictions being overturned and their release from detention in 2024 and 2023, respectively, and Clay being freed from jail in 2023.

Csicsila was aware of the sweeping nature of Operation Snake Doctor, as she helped coordinate it. She may have also been aware of the cell tower maps, extraction report, and alternative suspect evidence, but determining this has been difficult. CPD has severely redacted correspondence between Csicsila and CPD officers released under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). And although she wasn’t officially a prosecutor on the homicide cases, her emails with state prosecutors suggest she was kept in the loop to at least some extent.

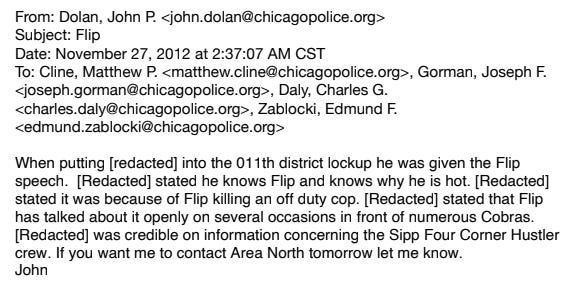

In addition to the undisclosed evidence, Blagg also discovered evidence CPD officers routinely told other Spanish Cobras during their interrogations that Villa was to blame for their arrests, to either entice them to implicate Villa in exchange for leniency, or provoke retaliation against him. This practice was so routine, it was internally dubbed the “Flip speech.”

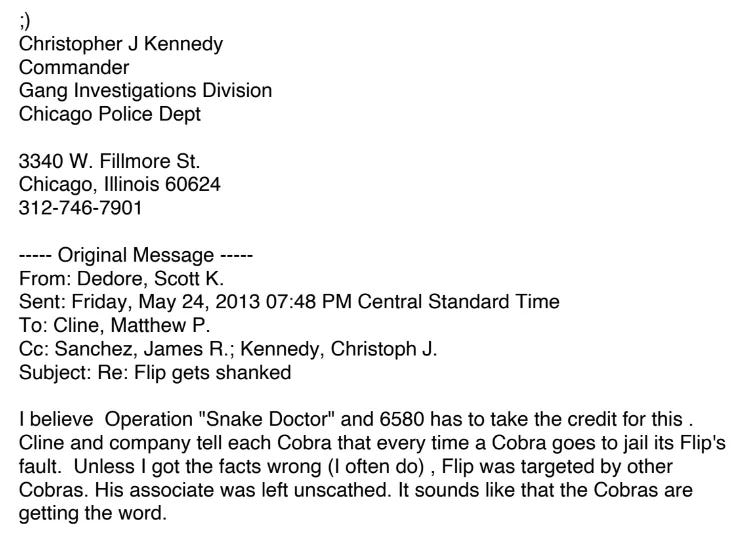

Officers appeared to believe the strategy worked after Villa was stabbed by another Cobra. They seemed to celebrate the outcome.

“I believe Operation ‘Snake Doctor’ and 6580 has to take the credit for this,” CPD Officer Scott Dedore wrote in an email. “Cline and company tell each Cobra that every time a Cobra goes to jail its Flip’s fault. Unless I got the facts wrong (I often do), Flip was targeted by other Cobras. His associate was left unscathed. It sounds like [the] Cobras are getting the word.”

Csicsila exchanged emails with CPD officers about Villa in the days leading up to his stabbing, and continued to do so after the incident, according to emails obtained by Noir and court filings from Villa’s state criminal case. It’s unclear whether she was aware of the nature of CPD’s interrogations of other Cobras.

The Angel Perez lawsuit

Operation Snake Doctor targeted many individuals affiliated with the Spanish Cobras gang, both for collecting intel on the Lewis homicide, and for securing federal narcotics convictions. One such target was Dwayne Payne, whose phone was being monitored by CPD and the feds via a Title III wiretap. In October 2012, law enforcement noticed Payne was in contact with a man named Angel Perez.

According to the lawsuit Perez eventually filed in June 2013 against CPD officers and the City of Chicago, CPD officers pressured him to cooperate in the investigation of Payne – specifically, to set up a controlled drug purchase. After refusing to cooperate, Perez alleges officers took him to a second-floor room at the secretive and controversial Homan Square Chicago Police facility, where they handcuffed him to a bar and placed him in ankle shackles for several hours. He alleges that officers threatened to plant evidence on him and send him “to the Cook County jail to be raped by gang members.” Perez further alleges that the officers continued to physically and verbally assault him for hours, and that one of them sodomized him with “a cold metal object, believed to be one of [the] officer’s service revolvers.” After the alleged torture, Perez relented and agreed to buy heroin from Payne for the officers. Perez’s calls to Payne, unbeknownst to Perez, were also being monitored through a Title III wiretap.

Emails released under FOIA show Csicsila was aware of and helped coordinate the wiretaps and was familiar with Perez’s role in the investigation.

In the fall of 2020, the defense in the Perez case sought to reopen discovery with the aim of obtaining the Title III wiretap recordings of Perez’s calls with Payne, which they hoped would show he cooperated in the Payne investigation willingly. Per their filing, Csicsila had originally indicated to them in conversations that they could obtain the recordings “because the criminal case against Payne had concluded.”

But when the defense filed subpoenas to obtain the recordings from the DOJ, and then a motion to compel when it wasn’t provided, she reversed course. Though not a party to the civil case, the DOJ held custody of the wiretap recordings and was required to respond to the defendants’ motion. Csicsila, representing the government, argued Title III, as the Seventh Circuit Court has understood it, prohibits wiretap materials from being produced in pre-trial discovery in civil proceedings.

While the Seventh Circuit Court has been historically conservative on this matter, it doesn’t render Csicsila’s involvement in Operation Snake Doctor moot. The facts of the case, including Perez’s possession of what the defense described as essentially verbatim transcripts of the recordings, could have given another U.S. Attorney cause to interpret the application of precedent differently.

The judge largely agreed with Csicsila in the Perez case, and allowed the DOJ to withhold the recordings. Csicsila would go on to use this ruling as precedent in Villa’s civil rights case.

The Alexander Villa lawsuit

Villa filed a civil complaint against several CPD officers, state prosecutors, and other parties in February 2025, in which he alleged he was deprived of due process, maliciously prosecuted, and unlawfully detained and framed, among other counts.

In June 2025, an attorney for Villa filed a motion for permission to produce into discovery emails and email attachments containing information obtained from wiretaps, and thus covered under Title III. Importantly, Blagg, who was Villa’s post-conviction attorney and is now one of his attorneys in the civil case, had already obtained these materials – without a protective order or confidentiality markings. In response to subpoenas issued by Blagg in 2022, CPD’s tech department had sent over 287,000 internal emails directly to Blagg, without any internal review or confidentiality designations, and with no protective order in place.

In November 2022, a lawyer for the City of Chicago discovered CPD’s improper production to Blagg, as well as the Title III wiretap-related materials contained therein, and contacted Csicsila shortly thereafter, according to court records – meaning Csicsila was aware of the Title III materials sent to Blagg by late 2022.

Kristen Cabanban, Director of Public Affairs for the City of Chicago’s Department of Law, declined to comment, writing in an email to Noir that “ the City does not comment on ongoing litigation.”

Over the following months, federal prosecutors intervened to block further disclosure, with U.S. Attorney John Lausch sending letters invoking grand jury secrecy and state judges quashing defense subpoenas in deference to federal objections. To address the documents improperly produced to Blagg by CPD, the parties agreed to retroactive protective orders in all three criminal cases in April and May 2023.

After Clay and Colon’s cases were dismissed in June 2023 and Villa’s conviction was vacated in October 2024, the state criminal courts modified those protective orders to allow production of discovery material in the state criminal cases in subsequent federal civil litigation, first for Clay and Colon in late 2024, then for Villa in February 2025. Neither Csicsila nor anyone else at the DOJ objected to these modifications at the time, with Csicsila only intervening months later when Villa’s attorneys looped in the federal government to give it a chance to respond regarding their motion to disclose.

Csicsila filed a response arguing that the Seventh Circuit’s strict interpretation of Title III meant these materials couldn’t be produced in civil pre-trial discovery, citing the precedent of the ruling in the Perez case. Csicsila instead argued that any disclosure of Title III materials should occur “at the time of trial,” or “relatively close to” trial.

This time, Csicsila didn’t persuade the judge, who stated in an August 2025 court hearing that the government forfeited its objections by failing to intervene when the state criminal court modified the protective orders to allow discovery documents to be introduced in the civil cases. Csicsila said she did not recall if she was alerted to the protective order modifications at the time.

“If somebody knew about it at the time that the protective order was being modified to allow the production of materials received in the criminal case in civil cases and the government was aware that this Title III material was in there and said nothing about that, that is a meaningful omission,” Judge Matthew F. Kennelly said in the hearing. “If you don’t recall, that’s essentially – I take that as a concession that you were aware of it at the time – that the government was aware of it at the time and did nothing.”

Judge Kennelly also rejected Csicsila’s proposed remedy of producing the Title III wiretap-related materials close to the time of trial rather than during pre-trial discovery.

“It’s not a workable solution,” Judge Kennelly said.“The cat is so far out of the bag, the cat is in the next country at this point.” He then granted Villa’s motion, allowing production of the Title III materials.

Less than a week after this ruling, Csicsila withdrew from the case, and later that month left the DOJ entirely.

When Villa requested additional materials held by the City of Chicago that included Title III documents, the next attorney representing the United States, AUSA Ronald DeWald, did not object to pre-trial production of these materials under a protective order. Importantly, unlike the materials to which Csicsila’s arguments pertained, the federal government’s about-face on Title III disclosure can’t be solely attributed to Judge Kennelly’s ruling rejecting Csicsila’s arguments, as these documents had not already been produced to Villa in his state criminal case.

Erika Csicsila, the U.S. Attorney’s Office, attorneys for Villa, and attorneys for the CPD defendants in Perez’s civil case did not respond to requests for comment.

“[I]f one takes seriously the idea of prosecutors as ministers of justice, it arguably should apply in civil rights contexts too,” said Abbe Smith, Professor of Law at Georgetown University. “Prosecutors shouldn’t play the role of keeping evidence from parties in a civil lawsuit or from the public, especially where the public has a strong interest in understanding what law enforcement was doing.”

Note: Noir News is being represented by Loevy & Loevy in an ongoing FOIA lawsuit against the Chicago Police Department seeking documents related to Operation Snake Doctor. Loevy & Loevy are representing Alexander Villa in his civil rights lawsuit.

Intersting article!

Nice story! I liked the graphics showing the timeline