Before the clearing: Inside the University of Chicago encampment

Students advocate for the University to divest from Israel and weapons manufacturers, and argue for a multi-national, democratic and unified state in Palestine

The first thing I noticed was the music. I don’t speak Arabic, but every so often I could make out: “Falastin… Falastin… Falastin.” It was a soothing groove.

One thing was clear right away, the five-piece band playing at the University of Chicago encampment protesting the war in Gaza was pretty good.

Two members of the band were singers, and each time I heard them sing “Falastin,” I heard pain, frustration, sorrow, and hope. One thing I didn’t hear, curiously, was a lust for violence, or even rage. Given the nature of the conflict, I expected some bitterness, some bite.

But there was no bite. The encampment wasn’t just peaceful in the sense that I didn’t hear anyone calling for violence. You could actually feel the peace in the music, in the conversations, in the hugs exchanged by students and faculty. It was tranquil, meditative, utopian. This was the closest thing I’d seen to what I’d read some late 1960s hippy gatherings were like – but with less sex and drugs and more keffiyehs.

There was a sign in the encampment that read “Globalize the Intifada,” a slogan that may make people nervous or feel threatened — perhaps not entirely unreasonably given the violent resistance associated with the Second Intifada. But, at least given the conversations that I had in the encampment, I don’t think the Global Intifada most of the students had in mind was one of explosions. It seemed they were advocating a nonviolent struggle to push the University of Chicago and the United States to stop supporting the war in Gaza and to stop supporting the state of Israel as it currently exists.

After enjoying the music for a while, I approached a young man toward an opening of the encampment. He was tall and wore a black gator mask. Given where he was standing and his serious demeanor, I assumed he was gatekeeping the entrance. But when I asked him about whether I could go in and who I might be able to interview, he looked confused. I interpreted his look as conveying: “why the hell are you asking me for permission to do anything?”

He gestured toward a group of people who looked chatty, and I met Andrew, a Jewish, anti-Zionist student in the encampment. Andrew explained to me that anyone was allowed to enter and exit the encampment, including Zionists, so long as they weren’t there to “cause trouble” or take pictures of people’s faces without their consent.

While I do think the contemporary expectation of many activists that they can’t be photographed or recorded is unhelpful and contradictory (you want to protest publicly, but you want the luxury of privacy?), this was by no means the Soviet-style “Are you a Zionist” checkpoint entry questioning system I had heard was in effect at other campuses. The encampment effectively allowed freedom of movement, and it looked to me like it hadn’t impeded access to the University’s buildings.

Andrew, who didn’t want to provide his last name or be photographed, said he was a fourth-year undergraduate student at the University studying Jewish History and that he’d been involved in activism for Palestine for a few years.

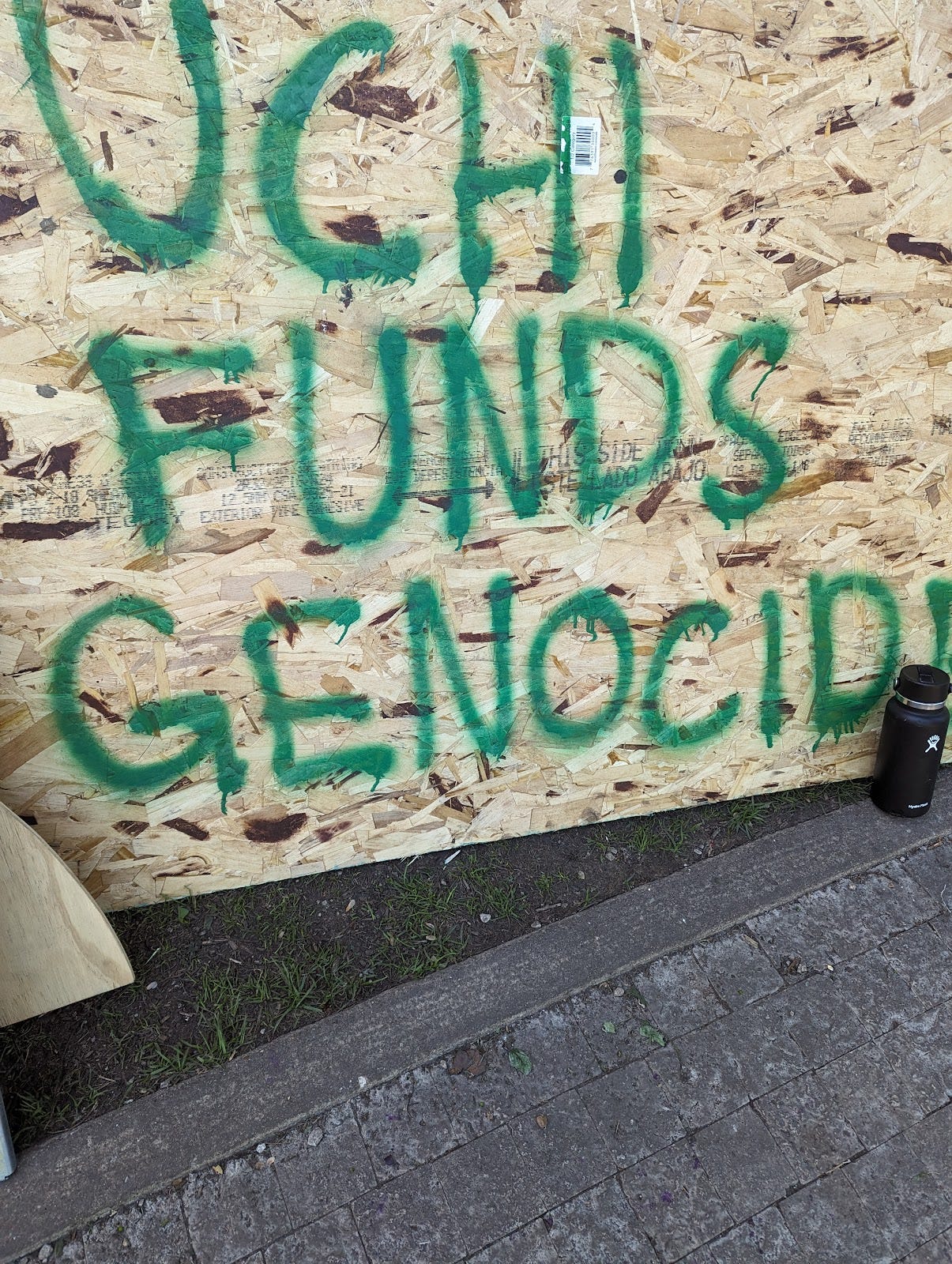

Asked why he was participating in the encampment, Andrew said: “The University of Chicago is very very deeply complicit in the genocide of Palestinians. Through its investments, through its various research connections to universities in Israel and corporations that function in Israel, study-abroads. There’s a real network of support that it offers for the Israeli Settler-Colonial project.”

He added that he wanted the University to divest from its investments in Israel and all weapons manufacturers, disclose all of its investments, and reparate the Palestinian people for the University’s role in harming them.

“It’s been great, a really wonderful community has emerged,” Andrew said.

I asked Andrew for his views on the Israel-Palestine conflict at large and whether, as some advocate for, Jewish people who came to Israel/Palestine in Zionist waves of immigration and their descendants should be made to leave.

“I speak for myself, not for the encampment. I think I see a single multi-ethnic, multi-national democratic state in the future,” Andrew said.

He did add that it would be hard to know what kind of solution would ultimately be feasible as Israel would likely have to suffer some kind of military or diplomatic defeat for any solution to be on the table.

After chatting with a few other students, each of whom were bright-eyed and very polite, I got three more students to agree to an interview: Jeffrey Sun, a fourth-year, Lukas Borja, a second-year and another UChicago student who preferred to remain anonymous, who we will call the First-Year.

Borja pulled out plastic buckets for sitting on. When I was about to sit on one of the buckets, he stopped me and gave me the sole nearby steel folding chair. I appreciated the back support.

The three of them explained why they came to the encampment. Sun said Israeli airstrikes on Gaza back in 2020, coupled with learning about the nature of propaganda in a class covering Nazi Cinema spurred his interest in advocacy relating to the conflict. Borja said he’d been participating in community-driven resistance for years, which he attributed to his indigenous identity. The First-Year said he was motivated by the principle that humanity as a whole can’t be free if any group is oppressed. All of their explanations were variations on a theme of wanting to end Palestinian suffering.

“We’re here because the bombing is still going on, houses are still being destroyed, and it's really necessary to not lose sight of that,” Sun said.

“We can't treat it as normal. Normal life should not involve genocide,” Sun added.

Borja said the encampment has been able to offer students and faculty perspectives on the conflict that they may not otherwise experience.

“We’ve had visiting, pretty regularly, people who were forced out during the Nakba, and their direct descendants,” Borja said. “Which offers a radically different perspective than what you'll get on the news.”

Like Andrew, the three students advocated for a unified, multinational state. They added that they desire the full right of return for displaced Palestinians.

Many worry that a one-state solution, paired with unlimited right of return for Palestinians, would inevitably result in either a genocide or ethnic cleansing of the Jewish people in a unified state in which they would now constitute an ethnic minority. This is not a worry solely articulated by Pro-Israel activists. The scholar Norman Finkelstein, one of the most prominent advocates for the Palestinian cause, has expressed skepticism about a bloodless implementation of a one-state solution.

The students may be right or wrong about the implications of a one-state solution with a full right of return for Palestinians. But what is clear is that the solution, as they envision it, does not involve an ethnic cleansing of Jews.

“The Palestinian state, as far we all understand it, is not derived around a quote ‘Arab Ethnostate’, where only Arabs can live there. I think everybody here, including a lot of the Jewish people here, know, at least I'm very aware and it's been emphasized in teach-ins, that Jewish people do have ancestral ties to Palestine. But they are not the only people who have ancestral ties. So I can't imagine a world where another Israel in reverse pops up,” Sun said.

The First-Year added: “By showing the solidarity that we are showing here, we are also showing that we do not fall into that contradiction of saying that: ‘oh we want only one group to be free, and all the expenses on the other one’,” The First-Year said. “We want to show that it is indeed possible for all of us to be free, it is indeed possible for all of us to have justice.”

Some days, not every day, I wear a Star of David necklace given to me by my dearest friend. I usually keep it tucked under my shirt when I go out – Jewish anxiety, I guess. I didn't pull it out when I went to visit the encampment. But I could have if I wanted to and no one would have batted an eye.

You might think the students at the encampment were wrong, silly or delusional. Maybe you think their views are bigoted or dangerous. Argue as you like on that.

But if I could commit anything to the historical record here, it would be that I didn't perceive any violence at the encampment. I felt young idealism and serene music.

The only moments I felt breaking up the serenity were students expressing fear that the University of Chicago’s police force would come to clear the encampment, given the University’s president saying that the school would intervene. They were right to worry: the encampment was cleared, beginning early the next morning, May 7.

Sam Carlen contributed to the editorial process for this article.

I was a UC student long ago, just before the anti-Vietnam-War movement picked up steam. What this piece describes shows me that today's UC students are as thoughtful and serious as ever. Best of everything to them!